Chapter One

Maria Cristina Terzaghi

Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo: Follow Up to a Discovery

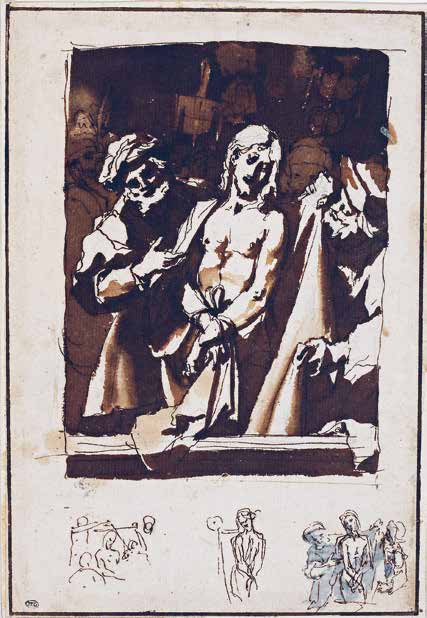

Milanese painter active around 1570 (Simone Peterzano?)

Ecce Homo, detail

Nantes, Musée des Beaux Arts

Then came Jesus forth, wearing the crown of thorns, and the purple robe. And Pilate saith unto them, Behold the man!

John, 19.5

Chapter One

Maria Cristina Terzaghi

At the beginning of April two years ago, an Ecce Homo that appeared in one of Madrid’s best-known auction houses with the unlikely attribution to a painter of Ribera’s circle, and a starting value of €1500, suddenly went viral.1 Indeed, it was almost unanimously attributed to Caravaggio, an absolutely unprecedented fact in the critical history of the painter, on whom scholars have rarely agreed, at least in the last forty years.2 The Ecce Homo is destined to leave a deep mark in the panorama of Caravaggio scholarship not only for the unexpected possibility of acquiring a new element to be inserted into the artist’s career, of the history woven around the painting and of the range of the questions that it raises on the painter’s creative process, of which I will try to give an account shortly, but also for reflection it provokes on the exercise of connoisseurship in general, and in the field of Caravaggio studies in particular. There are in fact at least three aspects that the appearance of the canvas has unrelentingly brought to the fore: the rapidity with which the critical debate took place, the singular nature of its venues, and the intertwining of critical positions, the market, preservation and the enhancement of knowledge.

The Media Launch

fig. 1

Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli

Ecce Homo

Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Galleria Palatina

The first report that something out of the ordinary was taking place in Spain appeared on Dagospia.com, the online Italian gossip site that followed the business of two society dealers: what were they doing in Madrid at a time when the planet was at a standstill in the grips of the latest lockdown? Apparently, there was a Caravaggio masterpiece to be had at a bargain price. Gossip definitely stole the show away from the discovery of the painting, its significance and even its correct attribution.4 From then on, within hours, an avalanche of more or less reliable information filled the pages of newspapers in Europe and the United States. On those same pages, hypotheses chased one another as to its market value, the attempts to acquire it, but also as to the provenance of the canvas, the first elements of which indeed surfaced intermittently in the columns of El País.5 There were those who thought it a scandal, and I do not deny that the media whirlwind was overwhelming. However, while speed is certainly a product of the new millennium, communication and critical debate in the pages of newspapers is not, at least not as far as Caravaggio is concerned.

The famed exhibition that can be considered the very beginning of modern studies on the artist, held in 1951 at the Palazzo Reale in Milan and curated by Roberto Longhi, filled the pages of the newspapers6 for the three months it remained on the billboard. From then on, the appearance of paintings by Caravaggio in newspapers would not be infrequent. I recall as a single example, since it is pertinent to the subject of the painting being presented here, the discovery of the Ecce Homo in Palazzo Bianco in Genoa, attributed to Caravaggio in the newspapers.7 But it is not only paintings, also the documents relating to the biography of the master that would make their first appearance in the press: his deed of baptism in Milan,8 and the account referring to the moneys collected in Rome from Ottavio Costa,9 for example. Caravaggio, in short, is among the very few “Old Masters” to have ever earnt a place on the front pages of newspapers, and in all likelihood always will be. Over and above the accuracy or otherwise of the trouvailles (which does not, however, depend directly on where these were announced), this extraordinary and growing interest does not seem, therefore, to signal so much the decadence of the times, but rather the extraordinary popularity of the artist from the day of his appearance on the modern and contemporary scene, an aspect that is not a incidental for critical reflection either. The appearance of autograph works in publications neither scholarly nor referenced scientifically, however, also opens up the no-less pressing question on the trustworthiness of attributions of paintings to the master. The role of the scholarly community is and will continue to be crucial in this regard. If there is one thing, however, that this Ecce Homo has brought to the fore, it is that despite the fact that connoisseurship does not work through a majority vote, the stylistic attribution of a painting will retain a character of objectivity: when, as in this case it is correct, then be comes easily shared.10

The Known and Unknown History of Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo

fig. 2

Attributed to Michelangelo Merisi known as Caravaggio

Crowning with Thorns

Prato, Galleria di Palazzo degli Alberti

Before delving into the iconographic and stylistic analysis of the Madrid Ecce Homo, it is necessary to first gather together the historical data relating to the painting, essential if we are to situate it in the artist’s career. Reference to an Ecce Homo painted by Caravaggio first appears in a text by Giovan Battista Cardi, nephew of the Florentine painter Ludovico Cardi, known as Cigoli, published in 1628: “Volendo Monsignor Massimi un Ecce Homo che gli soddisfacesse, ne commesse uno al Passignano, uno al Caravaggio et uno al Cigoli, senza che l’uno sapesse dell’altro; i quali tutti tirati a fine e messi al paragone, il suo piacque più degli altri, e perciò tenutolo appresso di sé Monsignore mentre stette a Roma, fu di poi portato a Firenze e venduto al Severi.”11 Clearly the author of the text wished to glorify his uncle’s painting, and the quotation should certainly be understood in this light; it is therefore important to understand what holds water and what does not in this narrative, putting together the pieces at our disposal of a puzzle on which various scholars have focused.12

The commission seems in fact to be confirmed by two documents in the private archive of the Massimo family, which scholarship has generally put in relation with it. The earliest, signed by Caravaggio himself, is dated 25 June 1605, and is a bond;13 the second, dated 2 March 1607, is instead a receipt for an advance payment of 25 scudi, signed by Ludovico Cigoli.14 The patron for both commissions, however, was Signor Massimo Massimi, and not Monsignor Innocenzo Massimi, who, according to Cardi, was the origin of the competition.15 In fact, on 25 June 1605, Caravaggio signs an undertaking to paint “Un quadro di valore e grandezza come quello ch’io gli feci già dell’Incoronatione di Cristo” (a painting of the same size and value as the one I already painted for him of the Crowning of Christ), for the “Illustrious Signor Massimo Massimi”, having already been paid for the work he was to carry out by the following August; while two years later, Cigoli received 25 scudi from Massimo Massimi for a “Quadro grande compagnio di uno altro mano del Sig.r Michelagniolo Caravaggio” (Large painting companion of another by the hand of Sig.r Michelagniolo Caravaggio). The canvas painted by Cigoli has been identified with certainty with the monumental and beautiful Ecce Homo in the Galleria Palatina in Florence [fig. 1], while Caravaggio’s canvas has been thought to be the Ecce Homo in Palazzo Bianco in Genoa [fig. 24, p. 67].16

I have already argued elsewhere how the latter identification is by no means a foregone conclusion: even leaving aside the attribution of the painting in Genoa to Caravaggio, which is far from certain, it is by no means clear whether the work commissioned from Caravaggio in 1605 was ever painted.17 According to Cigoli’s receipt, the documented commission could not have been part of a competition since the two works were not ordered concurrently, but at different moments in time. Another certainty is that the painting requested from Cigoli and the one by Caravaggio must have been pendants, this is in fact the most common seventeenth-century meaning of “quadro compagnio” (companion painting); the work in question is also unequivocally large: the payment specifies a “quadro grande” (large painting). Now, neither the Ecce Homo in Genoa nor the one in Madrid are of comparable dimensions to Cigoli’s painting now in Palazzo Pitti, but are considerably smaller.18 Caravaggio, on the other hand, most certainly painted a Crowning with Thorns generally identified with the painting which now hangs in the Galleria di Palazzo degli Alberti in Prato [fig. 2], the dimensions of which coincide perfectly with those of Cigoli’s Ecce Homo.

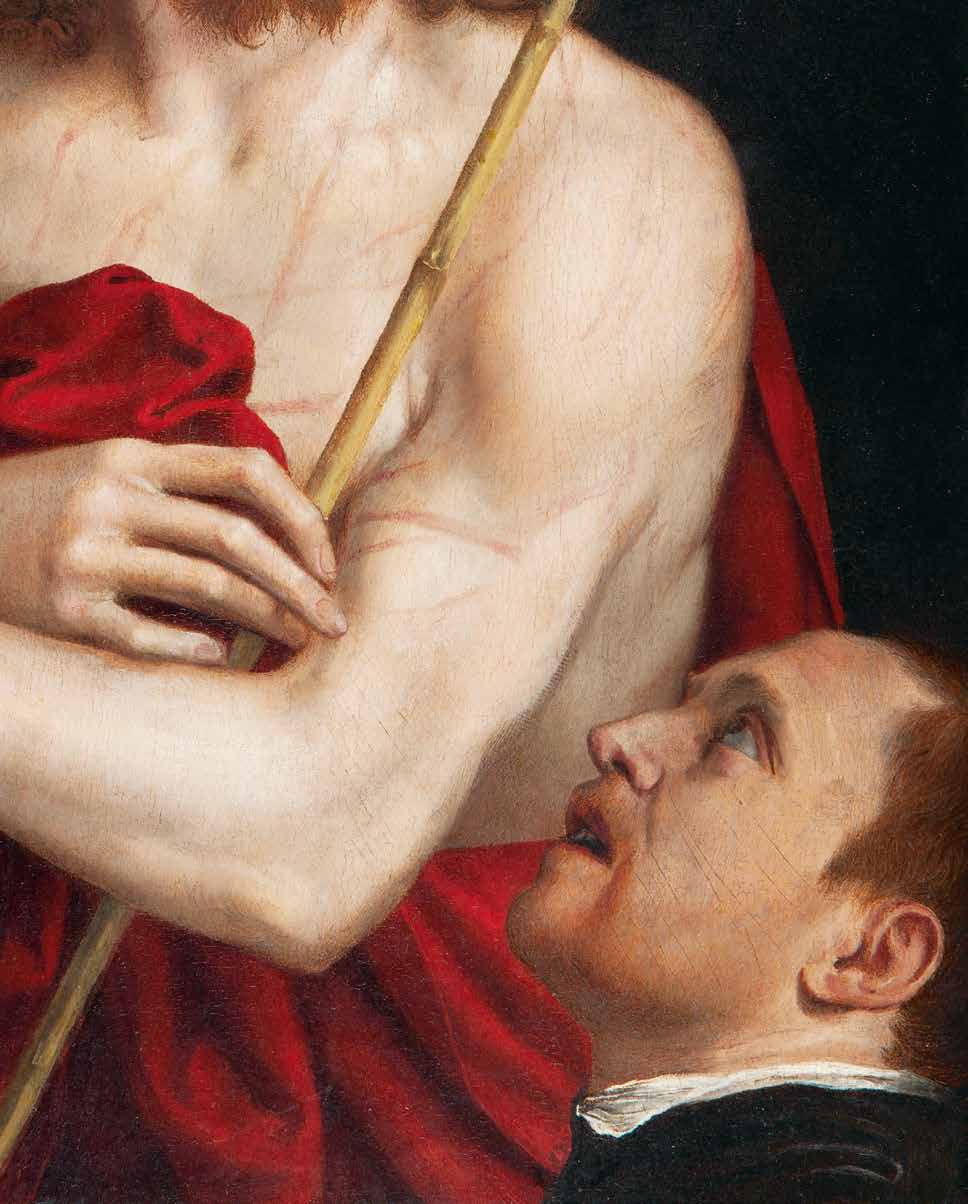

fig. 3

Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli

Ecce Homo

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins

It is therefore more likely that the commissions evoked in the two documents should be read in sequence: as the Lombard master had not completed the commission with which he had been entrusted, Massimo Massimi, having lost all hope of seeing the painter return to Rome, decided to commission Cigoli to execute the Ecce Homo that he had first asked Caravaggio to paint. The preparatory drawing for the Pitti canvas [fig. 3] also seems to confirm this reading, as three compositions, almost visual notes, are sketched-in along the lower margin. Two of them refer to ideas for the Ecce Homo, while the first to the viewer’s left is a Crowning with Thorns, and seems to be comparable to Caravaggio’s in the invention of the henchman in the foreground with his back turned to the viewer.19 It is therefore probable that Cigoli painted his Ecce Homo as a pendant for Caravaggio’s Crowning, while it is by no means certain that the latter artist had produced the promised painting even though he had already collected his fee, at least not before 1607, and therefore certainly not in Rome.20

In any case, in Massimo Massimi’s bedroom, the following remained: “Un quadro grande della Coronatione di spine di N[ostro] S[ignore] con cornice messe a oro, con coperta di taffetà rosso . . . un quadro grande dentro vi è un Ecce Homo con cornice messe a oro e un taffettano rosso per coprire detto Quadro.”21 The gentleman thus possessed two pendant works: a Crowning with Thorns and a large Ecce Homo. However, whether the author of the Ecce Homo was Cigoli, or whether it was Caravaggio, by 1644, the date of the nobleman’s post-mortem inventory, the painting would already have been far from Rome. Against the presence of Caravaggio’s canvas chez the Massimi is the testimony of Bellori, the only Roman source to mention the work. He refers to an Ecce Homo that Caravaggio had “colorito per li signori Massimi” (painted for the Massimi family), without specifying whether this was for Monsignor Innocenzo or for Massimo, nor does he mention a possible competition, adding that the canvas had been taken to Spain. Therefore, by 1645, when the scholar wrote his biography of Caravaggio, the painting was no longer visible in Rome.22

Moreover, at the time Cigoli’s painting had long since been moved to Florence, according to Cardi’s account of how the painting had been moved from Rome to Florence and thereafter ended up in the hands of the musician Giovan Battista Severi.23 This is endorsed by correspondence regarding an unsuccessful journey that the work made to Spain more than twenty years later, when the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinand II proposed it as a possible diplomatic gift to the King of Spain, and the Florentine ambassador to Madrid, Lodovico Incontri, sent the work back to Florence, judging it unsuitable for Philip IV’s taste. In the meantime, however, Incontri recounted that he was very familiar with the work, since on his advice, Don Lorenzo de Medici had bought it some twenty years earlier and then donated it to the court musician Giovan Battista Severi, who in turn had presented it as a gift to the Grand Duke.24 Knowledge of the work must have come directly via Monsignor Innocenzo Massimi, who held the position of Apostolic Nuncio in Florence between 1620 and 1621, and from there had moved to Madrid to the Spanish court in 1622, where he remained until May 1624, to then return to Rome. Having been appointed bishop of Catania, Innocenzo Massimi moved to Sicily in 1626 and died there seven years later, maintaining all the while close contact with the Spanish court.25 How then to explain the presence of the two paintings in the Massimi residence in 1644? The most probable solution is that in order not to deprive himself of the Ecce Homo, Massimo Massimi had procured a copy, whoever its author might have been, unless one were to hypothesize that Caravaggio had honoured his commitment to the gentleman at a later date, but in that case the painting would have had to be of a similar format to the Crowning, which means that it cannot be the Madrid painting.

But conjectures relating to the Massimi Ecce Homo do not end here. On the basis of the identification of the painting in Palazzo Bianco with the painting that Caravaggio may have painted in 1605, and the presence of copies of the work in Sicily,26 it has been suggested that the painting should be identified with an Ecce Homo attributed to Caravaggio, recorded in 1631 with an exceptionally high valuation of 800 ducats, in the collection of Juan de Lezcano, secretary to Pedro Fernández de Castro, Spanish ambassador to Rome until 1616, and later viceroy to the court of Palermo, brother of Francisco de Castro, viceroy of Naples “Un eccehomo con Pilato que lo muestra al pueblo y un sayon que le viste de detras la veste porpurea. Quadro grande original del Caravagio y esta pintura es estimada en mas de 800 ducados.”27

I have shown elsewhere how in Lezcano’s inventory the large paintings were around 125 centimetres in height since “Quadros muy grandi” (Very large paintings), that is altarpieces,28 were also included in the inventory. This time, the dimensions of the painting fully correspond to those of the Ecce Homo in Madrid and another Ecce Homo attributed to Caravaggio, recorded in January 1657 in the collection of García Avellaneda y Haro Delgadillo (1588–1670) second Count of Castrillo, Viceroy in Naples from 1653 to 1659, at the time he returned to his homeland bringing with him a rich collection of paintings.29 In the inventory drawn up at the time of the departure of his wife Maria de Avellaneda for Madrid, two works by Caravaggio appear amongst the many paintings acquired during their Italian sojourn. One can be identified with no uncertainty with the Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist in the Palacio Real in Madrid [fig. 4], having been presented as a gift by the Count to King Philip IV, as is documented by the work registered in the inventory of the Alcázar in 1666.30 The other is an Ecce Homo which is described as follows: “Mas otro quadro de un Heccehomo de zinco palmos con marco de evano con un soldado y Pilatos que le enseña al Pueblo es original de m° Miçael Angel Caravacho.”31 In addition to the description, it should be noted that the dimensions of the painting leaving for Spain are absolutely compatible with those of the Ecce Homo in Madrid, taking into account that the Neapolitan palm, the unit of measurement used in the Viceroy’s inventory, corresponds to approximately 26.33 centimetres and therefore the height of the painting including the frame (which is explicitly referred to in the inventory) must have been approximately 131 centimetres compared to the 111 of the Madrid painting.32

In order to understand whether there may have been a transfer from the collection of Juan de Lezcano’s to that of the Viceroy or, perhaps a purchase of the work on the Neapolitan art market, the Spanish gentleman’s accounts for the period in which the painting was available for purchase (1653–1658) were carefully examined, but no trace of the painting was found. The search was also extended to Juan de Lezcano’s numerous bank transactions in Naples, unfortunately recorded without specific indications and therefore useless.33 The Viceroy was mainly engaged in purchases of fabrics and clothes, carriages, sculptures, but paintings are scarce. During the terrible pestilence that struck Naples in 1656, he had arranged for accommodation in a house overlooking the sea at Santa Lucia, to which he moved with his family.34 Among the few items of interest for our research is the recurring purchase of works representing Ecce Homos among the Viceroy’s favourite subject-matters, but never in association with a painting, as far as I was able to establish. One thing, however, is clear, the Count of Castrillo procured art objects in Italy not only for himself but also to supply Philip IV in Madrid, so the transfer of paintings from the gentleman’s collection to the royal collection may also have taken place through moneys received by Avellaneda from the King of Spain himself, and not only as gifts from the subject to his liege.

It is therefore possible to trace with a high degree of probability the transfer of the painting from Castrillo to its current owners through the royal collection. Indeed, we are certain that the canvas came to the Pérez de Castro family by inheritance from an illustrious ancestor, the Spanish diplomat Evaristo Pérez de Castro y Colomera (Valladolid, 1769 – Madrid, 1849).35 “Por su notorio amor a las bellas artes y su dedicacíon a ellas” he was appointed honorary academician of the Accademia di San Fernando in 1800, when only a little over thirty.36 At a later date, the diplomat was involved in an episode that decided the fate of Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo. In 1821, Evaristo selected four paintings from the freshly printed catalogue of works belonging to the Accademia against which he might exchange the Saint John the Baptist attributed to Alonso Cano that he owned [fig. 5].37

The academicians took the diplomat’s offer very seriously [fig. 6] and decided to use the unknown provenance of a work as a criterion for the selection of the painting to be exchanged, so that no one would be able to complain in the future. As a result of the requisitions following the conflict between the Spanish and the French, a large number of paintings whose ownership was difficult to follow or trace, were stored at the Academy at the beginning of the nineteenth-century. Although at first the Ecce Homo appeared to have no certain provenance, and was therefore chosen,38 from the investigation conducted by the secretary Juan Pasqual Colomer into all the Ecce Homo held in the Academy39 and from a later entry in the handwritten inventory of the picture gallery [fig. 7] we learn that the painting originated in the bequest of Manuel Godoy, Charles IV’s famous Secretary of State and passionate collector, and had therefore been in the Real Accademia di San Fernando since 1816.40 Previously, the canvas had been in the keeping of the Palacio de Buenavista, where it most probably arrived together with the sovereign’s possessions from the Real Casa de Campo, a reservoir of royal paintings that Godoy was allowed to draw on by Charles IV himself.41 An Ecce Homo attributed to Caravaggio is indeed registered as present in the Real Casa: “Vara y medio de alta y cinco cuartas escasa de ancho. Un Ecceomo con dos figuras más, en dos mil reales. Estilo de Carabajio” the dimensions of which (125 centimetres high) correspond Giovan Battista Caracciolo known as Battistello, Immaculate Conception with Saint Dominic and Saint Francis of Paola, detail, Naples, church of Santa Maria della Stella with only a slight difference to those of the Madrid Ecce Homo.42 The work thus seems to have belonged to the royal collections: its presence can also be traced between 1701 and 1702 in the private apartments of Charles II,43 and most probably in Philip IV’s inventory of 1664, in which the painting appears with an attribution to Gherardo delle Notti.44 Like the Salome in the Palacio Real, therefore, the Ecce Homo most probably reached the collection of the King of Spain through the Viceroy, Count of Castrillo.

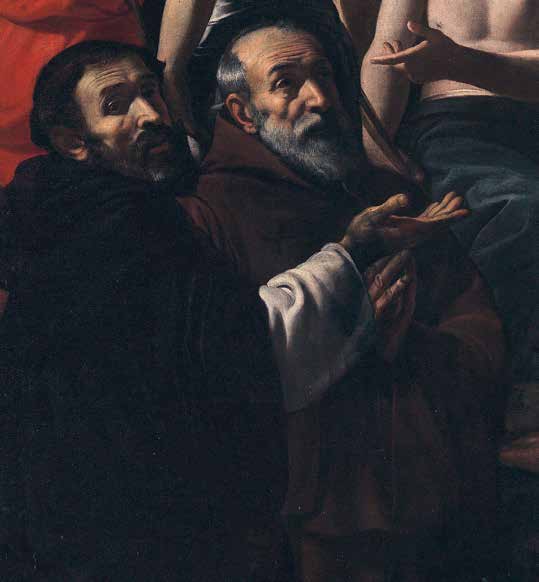

That the painting passed through Naples also seems to be confirmed by its influence on the local artistic milieu. For instance, we find similarities between the Saint Dominic painted by Battistello Caracciolo in the Immaculate Conception in Santa Maria della Stella [fig. 8] and the figure of Pilate [fig. 9], characterised by the same gestural expressiveness and position within the composition, which therefore can be linked not only to Caravaggio’s Madonna of the Rosary now in Vienna, but also probably to this Ecce Homo.45 The early date of Battistello’s masterpiece, certainly completed by 1608, could constitute a possible ante quem for the Ecce Homo, the as yet undulled palette and slightly rarefied handling of the paint in the work suggesting a date in the first period of Caravaggio’s Neapolitan sojourn.

From left to right

fig. 8

Giovan Battista Caracciolo known as Battistello Caracciolo

Immaculate Conception with Saint Domenic and Saint Francesco di Paola, detail

Naples, Chiesa di Santa Maria della Stella

fig. 9

Michelangelo Merisi known as Caravaggio

Ecce Homo, detail

Madrid, private collection

From left to right

fig. 8

Giovan Battista Caracciolo known as Battistello Caracciolo

Immaculate Conception with Saint Domenic and Saint Francesco di Paola, detail

Naples, Chiesa di Santa Maria della Stella

fig. 9

Michelangelo Merisi known as Caravaggio

Ecce Homo, detail

Madrid, private collection

At the Origins of the Painting’s Conception

From the moment of its appearance in Madrid, despite needing cleaning, the Ecce Homo has qualified as a work of exceptional painterly quality. The restoration masterfully carried out by Andrea Cipriani and his team, which is described in the following pages, has now revealed the expressive power of the painting in its entirety. One cannot fail to observe the power of its conception, the skilful compositional construction based on superimposed planes that restores a three-dimensional and dynamic scene that is entirely innovative, within the confines of an established iconographic tradition. When Donatello’s statues first appeared, Vasari wrote in the Proemio to the second part of his Lives, that the Florentines found themselves confronted with “pressoché persone vive, non più statue” (almost living people, and no longer statues). It is the essence of every artistic revolution, and this Ecce Homo is no exception.

The composition in itself is not novel: its references are the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century tradition, especially widespread in northern Italy and among northern artists, which envisaged the scene of Pilate presenting Christ to the people after the scourging and the crowning with thorns, one of the most dramatic moments of the Passion, recorded precisely solely in the Gospel of John (19:5). Erwin Panofsky, in his founding study dedicated to the iconography of the Gospel passage, distinguished between two moments of the representation: the first, the Ostentatio Christi, in which Pilate presents Jesus to the crowd, is more narrative; the second, on the other hand, focuses on the isolated figure of Jesus, generally half-length, laden with all the signs of the Passion and offered up for the contemplation of the faithful, giving rise to what is essentially a devotional image. Panofsky called this second iconography more appropriately: “Ecce Homo.”46

Subsequent studies have identified other ways of representing the subject, distinguishing between “Man of Sorrows”, “Christ in Pity”, “Ecce Homo” and “Christ Mocked”, not without noting how artists often represented several aspects of the Passion of Christ in a single image.47

Certain elements of the iconography described here were already present in the famous painting by Andrea Mantegna in Paris in the Musée Jacquemart André, datable to the beginning of the sixteenth-century,48 in which Jesus is depicted less than half-length, in a central position, surrounded by five figures, who accuse and mock him, one of whom with his mouth half-open; but Pilate is not among them. Again in the Venetian context, a significant role was played by the painting by Quentin Metsijs (or Massys) present in the Doge’s Palace in Venice, recorded with certainty at least since the sixteenth-century: the composition is in three-quarter view and behind the figure of Jesus in the centre, covered by a scarlet cloak and wearing a crown of thorns, crowd in two henchmen, one of whom has his mouth wide open. This model was also taken into account in other later examples with a decidedly less grotesque intonation, such as the beautiful painting by Titian in the Saint Louis Museum of Art, and, albeit in a different manner, in the celebrated example by Correggio in the National Gallery in London, a com- position also repeatedly translated into engravings [fig. 17].49

From left to right

fig. 10

Andrea Solario

Ecce Homo

Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli

fig. 11

Bernardino Luini

Ecce Homo

Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum,

Courboud Foundation

From left to right

fig. 10

Andrea Solario

Ecce Homo

Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli

fig. 11

Bernardino Luini

Ecce Homo

Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum,

Courboud Foundation

The idea, therefore, of the half-length or three-quarter-length composition with Christ in a central position surrounded by Pilate in oriental dress and with mocking soldiers, was in circulation in northern Italy. It is possible however to further restrict the figurative horizon that Caravaggio drew on to Lombard and Milanese works, with which he must inevitably have been familiar. The Ecce Homo is in fact a subject that was very dear to Leonardo’s circle, and Andrea Solario, not by chance active between Venice and Milan, was a specialist in it. In the Serenissima, in fact, in addition to possible incursions by Mantegna, were also undoubtedly present the Heads of Christ painted by Antonello, veritable source of inspiration for Solario’s works. Indeed, it is in the wake of Antonello’s works that David Alan Brown placed what appears to be the earliest example of Solario’s Ecce Homo depictions, now in the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan [fig. 10].50 But it is the work in Oxford, undoubtedly painted in Milan, that is of the greatest interest here, as Jesus is depicted between Pilate who points at him and in the foreground, close-up, a soldier—of extraordinarily sculptural quality—who taunts him [fig. 12]. Moreover, Christ’s body is marked by drops of blood in a decidedly more dramatic manner than in the Poldi Pezzoli panel, while the palette appears more varied. There is no doubt that Leonardo’s example, and in particular the dramatic relationship between Judas and Jesus established by Leonardo in the Last Supper, also changed the iconographic substance of the work, in this case becoming much more theatrical, with the extraordinary invention of the henchman entering the space from the right. Brown himself had already established a connection with the painting in Palazzo Bianco in Genoa (which he considers to be by Caravaggio), identifying in the Oxford panel the link between Mantegna and Caravaggio, despite not- ing inconsistencies in the Genoese painting which, in the light of the new painting presented here, are now more comprehensible.51 Without a doubt derived from Solario’s painting, is the later Ecce Homo by Bernardino Luini, now in Cologne, datable to the end of the third decade of the sixteenth-century [fig. 11].52 The influence of Solario on Luini’s Christ is evident, but the artist who most closely followed Solario’s example seems to me to be Giampietrino. The Milanese painter, a close follower of Leonardo, on several occasions represented the subject of Christ’s Passion: seated on a bench with green drapery,53 with the figure of Mary54 beside him, and finally— and this is the painting that is most relevant for us—with a soldier behind him almost swallowed up by the shadows [fig. 13].55 This latter work, despite the extreme difficulty of chronologically ordering the master’s paintings, certainly belongs to the artist’s maturity, in the 1530s. Although mindful of Solario’s example, it presents Jesus with his head turned to the right with the reed in his hand, in a manner strikingly similar to that of the Madrid Ecce Homo [fig. 15].

That the affinity between the two works is well-founded is proven by another painting presented here as a trait d’union between Giampietrino and Caravaggio. It is a panel painting of moderate size, but one that renders an image of extraordinary power [fig. 14]. Jesus is represented in the centre of the composition in a manner clearly similar to that of Giampietrino’s painting, of which it is a later transcription if not a true copy as on the right the beautifully painted head of a worshipper in profile stands out in front of the figure of the Ecce Homo, probably a portrait, gazing fixedly in contemplation of the Mystery of the Passion with his mouth wide open in an expression of devout wonder. Along the lower margin of the panel runs a thin white band bearing the inscription “REX MEUS ET DEUS MEUS.”56 The text appears in many Psalms (Ps. 83 for instance) and refers to the missal and the daily liturgy of the Hours. It is, therefore, a reference to a prayer probably uttered by the worshipper in front of the painting: a painting within a painting that results in an extraordinarily powerful conception and also clearly indicates the success of the image of the Ecce Homo by Giampietrino in the Lombard context.

The painting, which had passed through the art-market over a long period, entered the collections of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes a year ago as the work of a sixteenth-century Milanese artist. Previously, it had been cautiously compared to the early production of Giovan Paolo Lomazzo around the sixth decade of the sixteenth-century, and a generalised suggestion had been put forward of its possible derivation from a model by Giampietrino.57

Were we talking about Lomazzo or his circle, we could be sure that Caravaggio was familiar with his production,58 but I wonder whether an artist even closer to the very young Caravaggio might not also have been present at the crossroads between Milan and Venice at this time— namely Simone Peterzano. I must confess that my first impression of this extraordinary small panel was that of its close affinity with the Venetian master’s manner, which can be seen above all in the comparison between the portrait of the worshipper and the Self-portrait of the master recently donated by Maurizio Calvesi to the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo. A thin thread links this work, the Self-portrait in the Guise of Bacchus by Giovan Paolo Lomazzo in the Pinacoteca di Brera—which also had such a strong impact on the young Caravaggio—and the panel now in Nantes, which can also be seen in close-range of the compositional cut adopted, which is emphasized by the inscription written in dark capital letters on a light-coloured strip running along the lower margin, no different to a caption, a fashion that was widespread in the 1570s and 1580s in Milan.

But returning to Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo [fig. 15], we are surprised to observe that the Sorrowful Christ depicted is the seventeenth-century twin of the one contemplated by the worshipper in the Milanese panel, who in turn stood out before Giampietrino’s painting. Caravaggio, however, did not only rework the figure of Jesus from the Milanese painting, but also the idea of the superimposition of planes, of the figure who bursts into the scene from outside the plane of the painting in order to enter the spectator’s space. This is an idea which we have seen rooted in Milanese painting from Solario to the small panel in Nantes, and it is admirably taken up and at the same time brought up to date by Caravaggio. In the Madrid painting, Pilate leans out from the balcony, with extraordinary power; he is clothed in a dark garment with a strangely styled headdress, which has nothing to do with the figure often wearing sumptuous oriental clothing— and a turban, such as we see for example in the contemporary painting by Cigoli.

By contrast, Caravaggio’s Roman governor is dressed in the modern manner, wearing a dark garment common both to the Jewish tradition and to politicians between the 16th and 17th centuries, and is so characterised as to appear to all intents and purposes a portrait.59 The beautifully executed figure of the young henchman emerging from the shadows of the palace, which we can intuit almost rather than see, in a kind of fade-out, was already present to some extent in Giampietrino’s painting formerly on the art-market in Zurich. And it is precisely in this admirable invention that we can measure what Caravaggio’s thought owes to his Lombard past, but also his extraordinary innovative power. The young henchman is by no means a marginal, secondary character or confined to a negative role; he has completely lost the feral traits of the Northern tradition, to take on the role of a bystander who witnesses, transfixed, the Passion of the Just. With the scarlet cloak, he simultaneously veils and unveils Jesus’ body, his mouth falling open in an expression more of astonishment and resignation than one of mockery. In that half-open mouth, we now know, are condensed more than one hun- dred years of Milanese painting tradition straddling Solario and Peterzano, by way of Leonardo.

There is, however, one element that deviates from the Lombard repertoire identified up to this point, and that is the representation of the severed branch of the crown of thorns by means of a lighter brushstroke, so bright and luminous that it has led some to suggest a flame deliberately inserted by Caravaggio on Christ’s forehead with a strong symbolic value, perhaps alluding to the Holy Spirit [fig. 16]. 60 The scholars who have attempted to decipher this point of light, have done so more or less openly with the caution imposed by not having viewed the work directly, and moreover when it was also in need of cleaning.61 Now, the restoration is completed, it has become more evident how that brushstroke of light is congruous with the entire representation of the crown of thorns and constitutes its terminal part, at the juncture where, precisely, the branch has been snapped. Giacomo Berra, to whom we owe the most in-depth study on the subject, has clearly shown how the idea of the representation of the broken branch in the crown of thorns does not have an exclusively northern ancestry (from Dürer’s Christ in Passion onwards, to be clear), but is in fact put into circulation in Italian painting by Correggio’s Ecce Homo [fig. 17] referred to above, a popular model also thanks to the copies made, as well as engravings, with which Caravaggio could, therefore, have been familiar.62

Berra concludes by placing Caravaggio’s choice in the wake of the painter’s vocation for realism, albeit filtered through sixteenth-century artistic tradition.63 Personally, I am certain that Caravaggio could have been familiar with the work of Correggio, whose inventions circulated in Milan when the young Caravaggio was studying there; representing the avant-garde, they would have been fuel for an adolescent as alert and rebellious as Simone Peterzano’s apprentice. However, it would be reductive to confine that detail to an extreme desire for realism: Caravaggio—as, above all Roberto Longhi, Mina Gregori and Mia Cinotti have taught us–was first and foremost a painter. That possibility of a glimmer of light in the darkness of the whirlpool of thorns must have exercised an irresistible fascination on his artistic sensibility, as well as constituting the fissure through which the light of a possible good shimmers in the darkness of the Passion, that of Christ and that of Caravaggio himself: more than a tragedy, an infinite, endless drama. The figure of Jesus crowned with thorns, bathed in light, breaks away from the naturalistic representation of the two characters who accompany him to the balcony, and this also in the painterly handling, since, as we have seen, the master resorts to an image dear to Lombard devotion and not to painting from the model, the first and perhaps only time in his repertoire. And therein also lies the exceptional nature of this painting. It admirably illustrates an, as yet unseen, aspect of Caravaggio’s works: in the depiction of this precise moment of the Passion, Caravaggio in fact unites narrative with contemplation, showing us how it too has to do with the human condition, the true one.

Endnotes 1–10

[1] Oil on canvas, 111 × 85 cm, attributed to “Círculo de José de Ribera”, Ansorena, Madrid, auction 8 April 2021, lot 229.

[2] I refer to appearances of Caravaggio’s works after 1988, the year of the publication of the Cardsharps now in the Fort Worth Museum. For the immediate success of the Ecce Homo, I refer you to M. Cuppone, “Offerte critiche nella rassegna stampa,” in V. Sgarbi, Ecce Caravaggio. Da Roberto Longhi a oggi, Milan 2021, 82–115 and M. C. Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial. Un nuovo Ecce Homo del Merisi,” in Caravaggio a Napoli. Nuovi dati, nuove idee, proceedings of the conference (Naples, Museo di Capodimonte, 13–14 January 2020), edited by M. C. Terzaghi, Todi (Perugia) 2021 (“Studi di Storia dell’Arte, Speciali 2”), in particular 94–196, 208 notes 16–29. I would also like to point out the contributions published after October 2021: M. Riccòmini, “Caravaggio a Madrid,” in Festschrift per Vittorio Sgarbi. Settanta scritti e altrettanti auguri, Fontanellato (Parma) 2022, 316–319 and A. Zuccari, “L’Ecce Homodi Madrid: un nuovo Caravaggio?,” in Cantiere Caravaggio, Rome, 325–330. Riccòmini’s text is rather surprising in that it publishes a purported letter that an un-named friend of Roberto Longhi’s, on a visit to the Pérez de Castro family in Madrid, is said to have addressed to Longhi in Florence in 1954, enclosing a picture of the Ecce Homo with the attribution to Caravaggio and a reference to Bellori’s text that we will be discussing. The sealed letter is said to have been found by Riccòmini himself in a volume that belonged to Longhi, and held at the Fondazione di Studi named after the great critic. I believe that the text is a literary invention, since the investigations conducted at the Foundation do not provide evidence of the scholar’s account.

[3] Although stern towards Italian studies on Caravaggio, I believe S. McTighe’s criticism (“The Italian Caravaggio, among Others,” The Burlington Magazine CLXIV, 1426 [January 2022]: 50–55) is useful in this regard. It forces us to question the place of philology in the interpretation of the painting. I hope that it may emerge from these pages that connoisseurship is the first and most essential critical act, and that stylistic and iconographic analysis of the work is indispensable to its interpretation.

[4] We are limiting ourselves to newspapers or websites; however, a few days earlier, on 27 March 2021 to be precise, the photograph of the painting had appeared on social networks, and in particular on Facebook where the antiquarian Andrea Ciaroni had posted a “selfie” alongside the painting exhibited by Ansorena, but without any follow up.

[5] We will be referring to these, as and when, in the notes to the text.

[6] Mostra di Caravaggio e dei Caravaggeschi, edited by R. Longhi, Milan 1951, re-ed. in R. Longhi, Studi caravaggeschi, I, Florence 1999, 59–135. On the exhibition and the critical debate aroused in the press, see A. Galansino, “Dossier del ‘Dossier Caravage’ di André Berne-Joffroy,” Prospettiva, 106–107 (April–July 2002): 58–117; P. Aiello, Caravaggio 1951, Rome 2019, 37–73; M. C. Terzaghi, “La Giuditta di Caravaggio e i suoi primi interpreti,” in Caravaggio e Artemisia: la sfida di Giuditta. Violenza e seduzione nella pittura tra Cinque e Seicento, exhibition catalogue (Rome, Palazzo Barberini, 25 November 2021 – 22 March 2022), edited by M. C. Terzaghi, Rome 2021, 48–50.

[7] R. Besta, M. Priarone, “Il dibattito sull’Ecce Homo di Palazzo Bianco: storia e fortuna di un ‘ritrovamento’ tra vicenda attributiva e ipotesi di provenienza, in Caravaggio e i genovesi. Committenti, collezionisti, pittori, exhibition catalogue (Genoa, Palazzo della Meridiana, 14 February 2019 – 24 June 2019), edited by A. Orlando, Genoa 2019, 34–44.

[8] Traced by Vincenzo Pirami, the document was first published by M. Carminati, “Caravaggio da Milano,” Il Sole 24 Ore 25 February 2007: 29.

[9] M. C. Terzaghi, “Lo scontrino di Caravaggio,” Il Sole 24 Ore 30 October 2005: 45.

[10] In agreement on this point is also V. Sgarbi, “L’Ecce Homo di Madrid,” in Sgarbi, Ecce Caravaggio, 30.

Endnotes 11–20

[11] Monsignor Massimi desiring an Ecce Homo that would satisfy him, he commissioned one from Passignano, one from Caravaggio and one from Cigoli, each without the knowledge of the other; all of which [works] were completed and then compared, and as he liked his [Cigoli’s] more than the others, Monsignore therefore kept it while he was in Rome, and it was later taken to Florence and sold to Severi”, G. B. Cardi, Vita di Ludovico Cardi Cigoli, 1628, edited by G. Battelli, Florence 1913, 37–38. Filippo Baldinucci, Notizie de’ professori del disegno da Cimabue in qua, Firenze 1681–1728, V (1728), 36 explicitly takes up Cardi’s account: “Aveva il Cigoli fatta quest’opera per Monsignore de’ Massimi il quale desiderando di avere una simile Sacra Istoria di mano di uno de’ maggiori uomini del suo tempo, diedene la commissione a tre pittori, senza che l’uno nulla sapesse dell’altro, e tali furono il Passignano, il Cigoli e ‘l Caravaggio; ma essendo tutti i lor quadri rimasti finiti, riuscì di si eminente perfetione quel del Cigoli, che quel Prelato diede via i due, e questo solo a sua devozione si riservò. Seguita poi la sua morte, fu il quadro venduto a Giovanni Battista Severi, celebre musico del Serenissimo Principe don Lorenzo di Toscana, e condotto a Firenze, e da questo passò nella Serenissima Casa” (Cigoli had executed this work for Monsignore de’ Massimi who, wishing to have such a Sacred subject by the hand of one of the great men of his time, he gave the commission to three painters, each knowing nothing of the others, and these were Passignano, Cigoli and Caravaggio; but when all their paintings were finished, Cigoli’s was of such outstanding perfection, that the Prelate gave away the other two, and this work alone he reserved for his devotion. After his death, the painting was sold to Giovanni Battista Severi, famous musician of the Most Serene Prince Don Lorenzo di Toscana and taken to Florence, and from there it passed into the Most Serene House).

[12] The various positions are summarised by F. Curti, “Gli Ecce Homo di Caravaggio nei documenti e nelle fonti letterarie,” in Sgarbi, Ecce Caravaggio, 41–47 and Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial, ” 202–206, who were not able to take into account each other’s publications as they came out at the same time. To these should be added M. Massimo, “‘Volendo Monsignor Massimi un Ecce Homo…’; svelato l’ideatore della famosa gara pittorica tra Caravaggio, Cigoli e Passignano?,” in aboutartonline.com, 17 October 2021. I note here that my friend and colleague Francesca Curti also emphasises how the story of the competition may have been constructed by Cardi to exalt Cigoli’s painting in competition with the most celebrated artists in the Florentine sphere. Gianni Papi comes to the same conclusions in his essay in this same volume.

[13] As Curti, “Gli Ecce Homo di Caravaggio,” 41–43, argues this point in detail.

[14] For both documents, see R. Barbiellini Amidei, “Io Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Ancora a Palazzo Massimo,” Art & Dossier 18 (1987): 14–15 and R. Barbiellini Amidei, “Della committenza Massimo,” in Caravaggio. Nuove riflessioni, “Quaderni di Palazzo Venezia”, 6, 1989, 47–69.

[15] The first scholar to suggest Innocenzo Massimi as the originator of the competition was F. Faranda, Ludovico Cardi detto il Cigoli, Rome 1986, 154. On Innocenzo Massimo see the detailed contribution by D. G. Cueto, “I doni di monsignor Innocenzo Massimo alla corte di Spagna e la crisi di uno stile diplomatico,” in L’arte del dono. Scambi artistici e diplomatici tra Italia e Spagna, 1550–1650, edited by M. von Bernstoff, S. Kubresky-Piredda, Rome 2013, 201–221.

[16] On the Palazzo Bianco canvas first attributed to Caravaggio by Roberto Longhi and its abundant critical reception, see in particular the exhibition catalogue Caravaggio e i genovesi. It is interesting that research conducted on the Genoese painting has, very honestly, left open the possibility that this painting had nothing to do with the Massimi commission (Besta, Priarone, “Il dibattito sull’Ecce Homo,” 39–41). It is also worth noting that Anna Orlando (“Note sull’autografia dell’Ecce Homo di Palazzo Bianco e sulla sua possibile sicilianità,” in Caravaggio e i genovesi, 63–65), referring to a suggestion by Maurizio Marini, quite rightly sees in the figure of Pilate a re-proposition of Sebastiano del Piombo’s Portrait of Andrea Doria in the Palazzo del Principe in Genoa. This resemblance, in my opinion unquestionable, removes the possibility that the work was executed in a context such as the alleged Massimo competition, which had nothing to do with the Doria, and seems instead to be a lead in the direction of the powerful Genoese family.

[17] I am pleased that Massimo (“Volendo Monsignor Massimi”) came to the same conclusion, but he does not cite previous literature, in particular: E. L. Goldberg, “Spanish Taste, Medici Politics and a Lost Chapter in the History of Cigoli’s ‘Ecce Homo’,” The Burlington Magazine CXXXIV, 1067 (February 1992): 102–110; Cueto, “I doni di monsignor Innocenzo Massimo,” 201–203; Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 202–206. For an alternative view of the vexata quaestio, see Gianni Papi in his essay in this same volume.

[18] The only element that can be linked to Massimo’s receipt is in fact the Ecce Homo in Palazzo Pitti, the passage of the painting through Florence will be dealt with below, and it is on this that the argument must be based.

[19] I have already expressed this idea in Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 206. Although reaching conclusions that to some extent differ, the importance of the drawing is also underlined by Curti, “Gli Ecce Homo di Caravaggio,” 46–47.

[20] On the basis of the bond cited above, Besta, Priarone, “Il dibattito sull’Ecce Homo,” 40 and Curti, “Gli Ecce Homo di Caravaggio,” 48–53, present the execution of the work as a certainty.

Endnotes 21-30

[21] “A large painting of the Crowning with thorns of Our Lord with a gold frame and a red taffeta cover . . . a large painting with an Ecce Homo with a gilded frame and a red taffeta cover”, L. Sickel, Caravaggios Rom. Annäherungen an ein dissonantes Milieu, Berlin 2003, 247. On this issue see also F. Nicolai, Mecenati a confronto. Committenza, collezionismo e mercato dell’arte nella Roma del primo Seicento. Le famiglie Massimo, Altemps, Naro e Colonna, Rome 2008, 28–33, who states that in 1696 only the Crowning with Thorns remained in the Massimi household.

[22] G. P. Bellori, Le vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti moderni, Rome 1672, edited by E. Borea, Turin 1976, re-ed. 2009, 223.

[23] Cardi, Vita di Ludovico Cardi Cigoli, 37-38.

[24] On 7 October 1650 from Madrid, Lodovico Incontri to Giovan Battista Gondi, the Grand Duke’s secretary: “So molto bene che pittura & quella, havendola per mio mezzo comprata vent’anni fa incirca il Serenissimo Principe Don Lorenzo di gloriosa memoria et data a Giobattista Severi, et da questo donata all’Altezza Sua, poiché allora si fece vedere dal Commodi, et dal Birivelti, et non fu stimata fra le meglio opere che havesse fatto il Cigoli, et solo amirorno la franchezza de colpi, il che malamente è conosciuto dagl’altri che non sono professori, anzi a molti sodisfa meno che le pitture fatte con diligenza et ben colorite dal predetto Cigoli” (I know that painting very well, the Most Serene Prince Don Lorenzo of glorious memory having bought it through me about twenty years ago given it to Giobattista Severi, and by the latter then donated to His Highness, it was then seen by Commodi, and Birivelt, and was not esteemed among the best works that Cigoli had painted, and only admired for the frankness of the brushwork, which is poorly valued by those who are not professors [knowledgeable], indeed to many is less pleasing than the paintings executed with diligence and well painted [finished] by the aforementioned Cigoli), cf. Goldberg, “Spanish Taste, Medici Politics and a Lost Chapter,” 109.

[25] On all of this see Cueto, “I doni di monsignor Innocenzo Massimo,” 201–221.

[26] The best-known is in the Museo Regionale in Messina. For recent details on Sicilian copies, see G. Papi, “L’Ecce Homo giovanile di Caravaggio e le sue copie,” in Originali, repliche, copie, uno sguardo diverso sui grandi maestri, edited by P. Di Loreto, Rome 2018, 103–110; Besta, Priarone, “Il dibattito sull’Ecce Homo,” 40–41; Orlando, “Note sull’autografia dell’Ecce Homo,” 46–47. Valentina Certo has on several occasions between 18 April and 31 October 2021 in aboutartonline.com discussed the Messina sources regarding Caravaggio.

[27] “An eccehomo with Pilate who shows him to the people and a henchman seen from behind, [with a] crimson (‘purpurea’) robe. Large painting by the hand of Caravaggio and this painting is valued at 800 ducats”, A. Vannugli, “Il segretario Juan de Lezcano e l’Ecce Homo di Caravaggio,” in España y Napoles. Coleccionismo y mecenazgo virreinales en el siglo XVII, edited by J. L. Colomér, Madrid 2009, 267–276, and A. Vannugli, “La collezione del segretario Juan de Lezcano. Borgianni, Caravaggio, Reni e altri, nella quadreria di un funzionario spagnolo nell’Italia del primo Seicento,” Atti dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Classe di Scienze morali, storiche, filologiche CDVI, (2009): 322–539.

[28] Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 202.

[29] The important inventory: Inbentario de las Halaxas que hay en la Guardarropa del Conde de Castrillo mi señor Haviendose reconozido en el mes de Henero de 1657, in the private archives of the Count of Orgaz, who now holds the noble title of Castrillo, was published by B. Bartolomé, “El conde de Castrillo y sus intereses artísticos,” Boletín del Museo del Prado 33 (1994): 15–28.

[30] Bartolomé, “El conde de Castrillo,” 19–20. The inventory highlighted in relation to the Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist by J. Milicua, “Caravaggio. Salomé con la cabeza de San Juan Bautista,” entry in Caravaggio, exhibition catalogue (Madrid, Museo del Prado, 21 September – 21 November 1999; Bilbao, Museo de Bellas Artes, 29 November 1999 – 23 January 2000), edited by C. Strinati, R. Vodret, Madrid 1999, 138–141 and J. Milicua, “Caravaggio. Salomé con la cabeza de San Juan Bautista,” entry in Caravaggio y la pintura realista europea, exhibition catalogue (Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 10 October 2005 – 15 January 2006), edited by J. Milicua and M. M. Cuyás, Barcelona 2005, 80–85, then M.C. Terzaghi, “Caravaggio. Salomé con la cabeza de San Juan Bautista,” entry in De Caravaggio a Bernini. Obras Maestras del Seicento Italiano en las Collecciónes Reales, exhibition catalogue (Madrid, Palacio Real, 7 June – 16 October 2016), edited by G. Redín Michaus, Madrid 2016, 122–129.

Endnotes 31-40

[31] “Then another painting of a Hecce Homo measuring five palms, with an ebony frame, featuring a soldier and Pilate showing him to the people, is [an]original by the master Miçael Angel Caravacho”, Bartolomé, “El conde de Castrillo,” 25.

[32] I carried out the research on the bank accounts of two of the viceroy’s agents Gio. Matteo de Salazar, his secretary, and Gio. Matteo de Salas y León, in the Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli to whom I offer my sincere thanks for their precious collaboration. It would take too long to list here all the material found regarding the purchases of silver, clothes, horses, many to be sent to Madrid, as well as all the money spent to prepare the festivities in honour of the emperor’s election that was celebrated with great pomp in Naples. Here follows a list of the registers examined which do not cover all the years indicated because from 1653 to 1656 the documentation is incomplete: ASBNa, Banco di San Giacomo, Giornale di cassa and Giornale di banco, 1657, second semester, matr. 238, 239, 240, 241, 242, Giornale di cassa and Giornale di banco, 1658 first and second semester, matr. 247, 248, 249, 250, 251.

[33] For Juan de Lezcano the period examined runs from 1621 to 1631, the accounts are spread over three banks on which extensive sample checks were carried out, but references for the disbursements did not emerge.

[34] ASBNa, Banco di San Giacomo, cashbook, matr. 238, c. 187, 6 October 1657.

[35] On the whole affair and the relative documents, see Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 196–200, with a full reconstruction and with more bibliographic references, including those relating to the cultural importance of the figures involved.

[36] “For his well-known love of the fine arts and his devotion to them.” On the figure of the diplomat in relation to his artistic interests, I refer you to Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 196-197, where all earlier studies are referred to.

[37] Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, oil on canvas, 204 × 128 cm, inv. 495, datable around 1645–1650. On the attribution, see in particular J. L. Requena Bravo de Laguna, Princeps Monachorum: Arte e Iconografia de San Juan Bautista en los siglos del barroco hispano, doctoral thesis, Universidad de Navarra: https://www.academiacolecciones. com/pinturas/inventario.php?id=0495. For the exchange, see E. Navarrete Martínez, La Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando y la pintura en la primera mitad del siglo XIX, Fundación Universitaria Española, Madrid 1999, 270; I. Arana, “Un catalogo de Pedro Mandrazo de la collección de pintura de la Academia de San Fernando,” in Nuevas contribuciones en torno al mundo del coleccionismo de arte hispánico en los siglos XIX y XX, Somonte-Cenero, Gijón, 2013, 25; G. Altares, A. Marcos, “El viaje y la permuta de un ‘Caravaggio’,” El País 24 April 2021.

[38] Arana, “Un catalogo de Pedro Mandrazo,” 25: “El Ecce- Homo non se de donde vino pues en el inventario de pinturas recogidas en casa de Manuel Godoy no consta un quadro del tamaño com el que tiene el de Caravaggio, por lo que me parece (sin prejudicio que l’Academia disponga) se le podria cambiar” (I do not know where the Ecce-Homo came from, because the inventory of paintings in Manuel Godoy’s house does not show any painting of the size of the the one by Caravaggio, so it seems to me [subject to any provisions of the Academy] that it can be exchanged). In the document cited by Navarrete Martínez, La Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, 370, footnote 184, it is stated that on 16 February 1823, the Academy gave the go-ahead for the exchange by declaring that the painting: “No constando perteneciese a ningún particular ni corporacion” (Does not belong to any private individual or corporation).

[39] Archivo de la Real Academia de San Fernando (henceforth ARABASF), 1-36-1, 5 February 1823, loose documents. The document, too long to reproduce here in full, has been published in full in Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 198.

[40] ARABASF, 3-620: Copia del Inventario general sus acdiciones pertineciente à la Academia de nobles artes de S. Fernando, c. 44r-v. This document (archival shelfmark aside), was first reported by A. Lucas, “El posible Caravaggio pertenenció a Godoy antes de llegar a la Real Academia,” El Mundo 29 April 2021; A. Lucas, “Así se cambió un Alonso Cano por un ‘Ecce Homo que se cree ser del Carabaggio’,” El Mundo 30 April 2021. In the text another document is also illustrated, namely the manuscript volume Actas Real Academia Bellas Artes de San Fernando. 1819–1830 (this is the correct shelfmark: ARABASF, 88/3) in which, however, there is no indication of provenance from the Godoy collection, only the exchange itself is recorded.

Endnotes 41–50

[41] Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 200.

[42] “A vara and a half in height and a scant five quarters wide. An Ecceomo with two other figures, valued at two thousand real. Style of Carabajio.”, Fernando Fernández Miranda, Inventarios Reales: Carlos III. Tomo II, Madrid, Patrimonio Nacional 1989, 452, no. 4598, see Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 200–201.

[43] Gloria Fernández Bayton, Inventarios Reales: Testamentaria del rey Carlos II. Tomo II, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, 1981, 201, no. 52: “Alcoba de su magestad . . . Otra Pintura de un Eccehomo de Vara y media de alto con marco negro tasado en sesanta doblones” (His Majesty’s Bedroom . . . Another painting of an Eccehomo of a vara and a half in height, with a black frame, valued at sixty doubloons). The reference has been linked to that of Charles III’s inventory, and the Ecce Homo which passed through Ansorena, by S. G. Moreno, H. San José, “El Caravaggio procede de la Colección Real,” Ars Magazine. Revista de Arte y Colecciónismo 50 (April–June 2021). It should be noted that, as difficult as it may seem to believe, the subject is seldom represented in the Royal Collections, so the search is simplified and, as in this case, in the absence of other works on the same subject, can also be based on dimensions alone.

[44] With number 410: “Otra pintura, de bara y quarta de alto y bara de largo, [circa 105 × 84 cm] con moldura de ébano, Cristo quando le muestran el pueblo, de medias figuras, de mano de Jerardo, ed ducientos y cinquenta ducados de plata” (Another painting, one vara and a quarter high and one vara wide [about 105 × 84 cm], with ebony frame, Christ being shown to the people, with half-length figures, the work of Jerardo, and two hundred and fifty ducats of silver) (Terzaghi, “Caravaggio millennial,” 201).

[45] M. C. Terzaghi, “Battistello and Caravaggio in context,” in Il patriarca bronzeo dei caravaggeschi. Battistello Caracciolo. 1578–1635, exhibition catalogue (Naples, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte – Palazzo Reale – Certosa e Museo di San Martino, 9 June – 2 November 2022), edited by S. Causa, Naples 2022, 65–66.

[46] E. Panofsky, “Jean Hey’s Ecce Homo. Speculations about its Author, its Donor, and its Iconography,” Bullettin des Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique 2–3 (September–December 1956): 102 ff.

[47] After Panofsky, the iconography of the Ecce Homo was included in the important volume by S. Ringdom, Icon to narrative: the Rise of the Dramatic Close–up in Fifteenth Century Devotional Painting, Turku 1965, 142–155. For a recent synthesis see the volume New Perspectives in the Man of Sorrows, edited by C. Puglisi, W. L. Barcham, Kalamazoo 2013, in particular on the iconographic theme, see C. Hourihane, “Defining Terms: Ecce Homo, Christ of Pity, Christ Mocked, and the Man of Sorrows,” in New Perspectives in the Man, 16–46.

[48] Oil on canvas, 54 × 42 cm, Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André. The painting’s importance for the iconography of Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo is also emphasised by Keith Christiansen in this volume.

[49] On the crucial role of Metsijs’ painting in the diffusion of the iconography in the Veneto, see M. Bellavitis, “Tra Fiandre e Italia, alcuni passaggi per un’iconografia dell’Ecce Homo,” in Citazioni, modelli e tipologie nella produzione dell’opera d’arte, Atti delle giornate di studio (Padova, 29–30 May 2008), edited by C. Caramazza, N. Macola, L. Nazzi, Padua 2011, 263–269. Keith Christiansen rightly also draws attention in the essay in this same volume to Quentin Metsijs’s Ecce Homo in the Prado Museum as a precedent for Caravaggio’s painting.

[50] Tempera and oil on panel, 43 × 33 cm, Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, inv. 1647/637. See D. A. Brown, Andrea Solario, Milan 1987, 71–72, cat. 9. For all other scholars, however, the work was executed in Milan within the first five years of the sixteenth- century.

Endnotes 51–60

[51] Brown, Andrea Solario, 110–113, 125, 149, cat. 31.

[52] Oil on panel, 71.5 × 56.7 cm, Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz- Museum, Courboud Foundation, inv. WRM 0528, on the painting now see C. Quattrini, Bernardino Luini. Catalogo generale delle opere, Turin 2019, 80, cat. 147.

[53] Panel exhibited at Sotheby’s, New York, 30 January 2014, lot 220.

[54] Oil on panel, 64.7 × 50.8 cm, private collection, cf. T. Kustodieva, “Ecce Homo di Giampietrino: due versioni di una composizione,” Ricche Minere 2 (2014): 21–30.

[55] Oil on panel, 63.3 × 50 cm, Koller Auctionen Zurich, auction no. 192, 19 June 2020, lot 3014.

[56] Oil on panel, 46 × 36.5 cm, formerly Geneva, Rob Smeets Old Master Paintings, and most recently auctioned at Hotel Drouot, Paris, 25 November 2021, lot 15.

[57] M. Pavesi, “Qualche riflessione sull’attività pittorica di Giovan Paolo Lomazzo,” in Studi in onore di Maria Grazia Albertini Ottolenghi, edited by M. Rossi, A. Rovetta, F. Tedeschi, Milan 2013, 157–161. The painting had been pointed out to the scholar by Francesco Frangi, who included the panel in his impressive review Giovan Girolamo Savoldo: pittura e cultura religiosa nel primo Cinquecento, Cinisello Balsamo (Milan), 2022, 78, note 215 without pre-judging the attribution, but identifying its first reference as an autograph work by Andrea Solario by A. Venturi, “Gruppo di cose inedite,” L’Arte XLI (1938): 67–68. I would add here that before passing through the Rob Smeets gallery, the work had appeared at an auction on 17 November 2008 (Mutual Art) as being by Andrea Solario, thus maintaining the first reference to its attribution as proposed by Venturi senior.

[58] On the relationship between Caravaggio and Lomazzo, which many studies have stressed, beginning with Roberto Longhi, via the even more detailed studies by Mina Gregori, and then those by Francesco Porzio and Giacomo Berra, see further developments and in-depth studies in M. C. Terzaghi, “Per le fonti del naturalismo di Caravaggio,” in Caravaggio e i letterati, edited by S. Ebert-Schifferer, L. Teza, Todi (Perugia) 2020 (“Studi di Storia dell’Arte, Speciali”), 79–97.

[59] Gianni Papi’s essay in this volume also focuses on Pilate’s clothing. Rossella Vodret, in finestresull’arte.info, 10 April 2021, suggests that Pilate’s face may conceal a self-portrait of the master dating from the Neapolitan period. I am grateful to Alessio Palmieri Marinoni for his advice on Pilate’s clothing: the black and red head covering would indeed correspond to the Jewish tradition.

[60] The first to identify such an iconographic element was Alessandro Zuccari, “La genialità dell’invenzione fa ritenere l’Ecce Homo autografo; e poi c’è un dettaglio…,” aboutartonline.com, 10 April 2021. In addition to Zuccari, Massimo Pulini has also argued in favour of a symbolic interpretation of the sign. “A colloquio sull’‘Ecce Homo’. Massimo Pulini ricostruisce la vicenda e conferma: La genialità dell’invenzione fa ritenere l’Ecce Homo autografo; e poi c’è un dettaglio…,” aboutartonline.com, 18 April 2021. For interpretations of the brushstroke as a severed branch without any symbolic reference: K. Herrmann Fiore, “Thematic observations on Ecce Homo in Madrid: ‘problematic’ the attribution to Caravaggio,” aboutartonline.com, 2 May 2021; S. Magister, “Sull’iconografia dell’Ecce Homo di Madrid,” in Sgarbi, Ecce Caravaggio, 47. On all aspects see G. Berra, “Il ‘ramo tagliato’ nella corona di spine dell’Ecce Homo di Madrid attribuito al Caravaggio,” in aboutartonline.com, 11 July 2021, 1–38.

Endnotes 61–63